We normally like to think about what causes competitive strategies to be successful. But a discussion of what causes them to fail can complement our understanding about what a good competitive strategy is and why a clear competitive strategy is so important for the for-profit firm.

Easy candidates for causes of strategy failure include:

- Misreading customers changing priorities and what they will pay for by offering new products and services that are not demanded. Did Apple’s Watch miss the mark or just ahead of its time?

- Bad execution of a sound strategy via botched operations initiatives that are not sequenced properly. This causes re-work and increases costs.

- Bad execution of a sound strategy via a lack of a sense of urgency and a lack of world-class speed. This causes missed windows of opportunity and can lower customer willingness to pay (because the firm is seen as a weak copycat) and increase costs due to re-work.

- Not making key trade-off decisions as the firm tries to be “all things to all people”. Here the firm becomes to be “stuck in the middle” from being a pure low cost/low price provider or a differentiator. The firm is stuck in a perpetual situation of costs being too high and prices too low relative to rivals. Not good news.

- Not using Lean Start Up principles and instead betting on a big homerun. Lean Start Up principles use a series of much smaller experiments with customers. The firm learns from early adopter customers and “pivots” with small iterations to get the offering to be demanded.

I could give more obvious causes for strategy failure, but I think the reader can add their own. But in my view the root cause of failure lies in the distinction between “single-loop” and “double-loop” learning. This notion was suggested by Chris Argyris of Harvard forty years ago and I have adapted it ever since to my practice of strategy. Let’s discuss this crucial topic.

Single-loop Learning

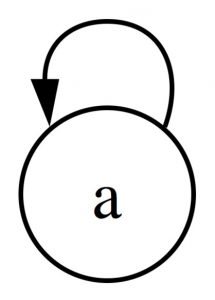

Single-loop learning is what we are all familiar with. A competitive strategy is set and planned financial performance is set for one to three years out. After the first year, Actual Performance is compared to Planned Performance. If Actual is less than Planned, there is a Performance Gap. Some firms are concerned if Actual is greater than Planned as to why their forecasting skills are not better, but Actual being greater then Planned is usually just celebrated. What is the strategist to do if there is a gap of Actual being less than Planned? He or she can fine-tune the strategy and re-forecast Planned performance. The next (second) year out the comparison is done again. And so the cycle continues until the strategy and Actual and Planned performance are brought into alignment.

Notice a couple of things with single-loop learning. The strategy itself is assumed to be sound. It is only fine-tuned in the annual comparison process. And notice the strategist can lower Planned performance to make it easier to align with expected Actual performance. This can be a formula for mediocrity though. No wonder in Martin and Lafley’s nice book Playing to Win, the first thing firms should ask themselves in their strategy formulation efforts is “What is Our Winning Aspiration”? Not how we can be like everyone else, but how we can win.

But notice the real trap that can happen in single-loop learning. Firms can go for five years or more in the annual tinkering process of aligning Planned and Actual performance and hide from the fact that the original strategy was not sound to begin with!!

Double-loop Learning

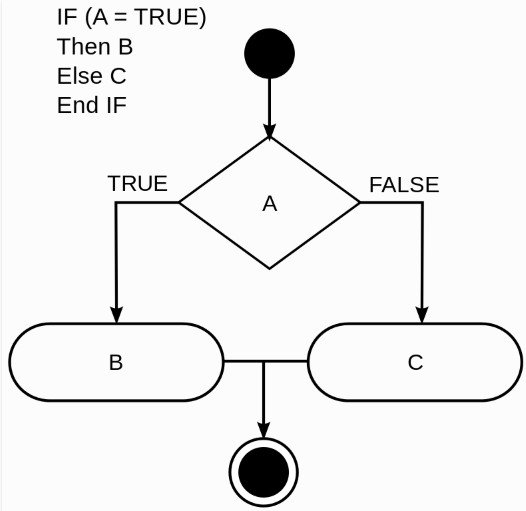

Enter double-loop learning. Here the strategist asks the question: “Why do we think the strategy will work in the first place”? I borrow again from Martin and Lafley. Here they ask the strategist to ask, “What must be true for the strategy to work”? Notice the question is not what is true, but what must be true. This is a great strategic thinking exercise.

In double-loop learning, a host of what I call culture barriers can prevent a management team from honestly asking and answering what must be true for the strategy to work and win. Faulty mental models, biases, fatigue, political in fighting and the like can zap the resolve to ask and answer the key question “what must be true”.

In my earlier article “Four Kinds of Barriers in the Established Firm” I chronicle the problems Encyclopedia Britannica had in double-loop learning. Let me give the reader an example that is plaguing me now in my firm. What I am about to write is not an advertisement. It is offered as an example of double-loop learning issues any strategist can encounter. I have developed a comprehensive strategic management framework called the Business Performance Engine. I have packaged what I have learned over the last thirty-five years about strategy, sustainable competitive advantage and winning. But it has turned out to be too complex. What is second nature to me is hard to understand for even the most seasoned strategy professional. Part of the problem is I introduce some new language. But the main reason is that it is just too comprehensive.

What did I really think had to be true to develop and launch this framework? It is, after a lot of soul searching, that there are a lot of senior executives who have followed a similar experience and learning journey to mine to appreciate what I conveniently packaged for them to use immediately in their strategy efforts. As it turns out, this is not true at all. Many of the executives who would have had the chance to appreciate the framework have retired. Notice even they may have not appreciated such comprehensiveness. But the real issue is that younger executives are on their own learning and experience journeys. My framework probably seems like a nuisance to them in their journey. As of this writing, I plan to scrap this offering and just use it myself in picking stocks for investment. But the learning here for you the reader is I would not have wasted a year and a half of hard work if I had asked the “What must be true” question first.

There are lots of things that cause strategies to fail. This is why good strategy is so important and valuable for firms. What are the things that “must be true” for your competitive strategy to win?

This article is part of a series on what causes a firm’s value to increase

Dr. William Bigler is the founder and CEO of Bill Bigler Associates. He is the former MBA Program Director at Louisiana State University at Shreveport and was the President of the Board of the Association for Strategic Planning in 2012 and served on the Board of Advisors for Nitro Security Inc. from 2003-2005. He has worked in the strategy departments of PricewaterhouseCoopers, the Hay Group, Ernst & Young and the Thomas Group. He can be reached at bill@billbigler.com or www.billbigler.com.