This is Part 2 of 2015’s third article discussing the possibility of the I-20 Corridor becoming the next Austin, Texas, a region that enables the creation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem to support torrents of new business venture creation.

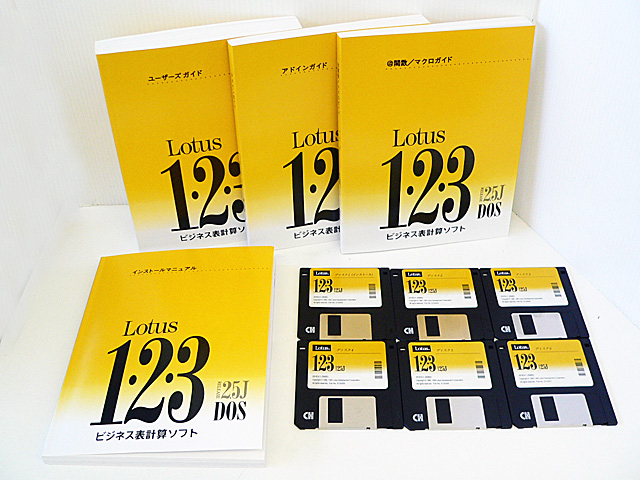

As we said at the end of Part 1, venture capital investing looks for major new startups. Usually, a group of venture capitalists form a fund to do this investing. For example, in the 1980s, Sevin-Rosen Funds of Dallas raised a series of $80 million dollar funds. They got rich in their first fund investing in Lotus 1-2-3, Compaq Computers and others. The sources of these funds are usually wealthy families, retirement fund managers looking for more returns on their retirement funds held under contract and in some cases the alternative investing arms of major corporations. Each fund is usually set up as a limited liability partnership with a general partner team investing on behalf of the sources, which are the limited partners.

As we said at the end of Part 1, venture capital investing looks for major new startups. Usually, a group of venture capitalists form a fund to do this investing. For example, in the 1980s, Sevin-Rosen Funds of Dallas raised a series of $80 million dollar funds. They got rich in their first fund investing in Lotus 1-2-3, Compaq Computers and others. The sources of these funds are usually wealthy families, retirement fund managers looking for more returns on their retirement funds held under contract and in some cases the alternative investing arms of major corporations. Each fund is usually set up as a limited liability partnership with a general partner team investing on behalf of the sources, which are the limited partners.

The limited partners are normally silent in this process and simply let the general managing partner team invest in startups up to the fund maximum. Once the maximum pool of money is invested, the fund is deemed closed. There is huge angst in this process as the general and limited partners want on average ten times their money within seven years. This is an average of 30-50% return on capital per year although some funds are happy with less return.

Thus the limiting aspect in venture capital is usually not the amount of money to be invested. It is the number of deals the general partner team can effectively manage to get these huge returns. Why the necessity of demanding such returns? It is due to the extremely high risk inherent in most major new venture startups. As a rule of thumb, the fund will lose money on eight out of ten investments and hit it big on one or two. These odds are not for the faint of heart.

To manage this risk, the funds usually focus on industries they know very well and also syndicate by inviting other funds to participate in the deals to spread risk. As I mentioned, all eyes are on these funds once they are closed and are expected to work their magic.

To manage this risk, the funds usually focus on industries they know very well and also syndicate by inviting other funds to participate in the deals to spread risk. As I mentioned, all eyes are on these funds once they are closed and are expected to work their magic.

Here is where I see some consternation and frustration in some new ventures in our region. They wonder why they are not getting funded after eight to ten “pitches” to various investor groups. It may be because their venture, while seeming related to other ventures a group has previously invested in, turns out to be very distant from their experience. Or the funds may actually be closed in that they are invested up to the max. Why then would such an investor group entertain proposals knowing they cannot now fund? It is because they are human like the rest of us and want to learn if some new, potentially rewarding industry is sprouting up for which they can raise a new fund, or at least participate via syndication via someone else’s fund. Many investor groups know and like each other and try to participate together. This issue of timing is very frustrating for the entrepreneur seeing months pass by and feeling they are spinning their wheels. Or lastly, and this is disappointing but hugely valuable, investors may know or sense a particular venture will not get out of the fatal flaws test, even if it can pass the smell test, and either fail or not provide the returns they expect. Entrepreneurs should be told at the earliest time knowledge is certain that their venture will simply not work in terms of expected return, or is destined for failure or should be viewed as a lifestyle startup and proceed incrementally with small amounts of family raised capital.

However, and many investors use different terms, there are many avenues available and have to do with the lifecycle of the venture. New ventures usually run the path of raising capital from personal and family money, to angels, to first stage investing, then second stage and then later larger rounds. Some even place what is called a mezzanine round of financing in between first and second stage funding. Many investment groups specialize on only one of these phases so the venture team doing its homework is key.

What does the I-20 Corridor need now? In my view it needs at least one fund at the $80 million range. Now some will retort we do not have that many ventures here yet to warrant such a fund. But I think the entrepreneurs would move here to avail of such funding.

We are in the chicken and egg conundrum. We need one new major win to come out of our ecosystem. And then energy and vision can really take hold for more capital, more investing and more winning new ventures. It is a virtuous cycle of wealth and job creation. We do need some luck but mostly a lot of hard and collaborative work among the entities listed in the first article of this series. One last thing: kudos to our entrepreneurs. Without your ideas, courage, stamina, fortitude and yes a good sense of humor, all of this dries up. We should never forget this.

Bill Bigler is Director of MBA Programs and associate professor of strategy at LSU Shreveport. He spent twenty-five years in the strategy consulting industry before returning to academia full time at LSUS. He is involved with several global professional strategy organizations and can be reached at bbigler@lsus.edu and www.strategybest.com