In 2019 time and speed are still important operational and strategic weapons for firms. Just look at Amazon moving to next day and now same day delivery. But the very rich disciplines of process innovation and process management seem to be disappearing in many or even most firms. This article, part of my series on what causes the valuation of the for-profit firm to increase, will in part be a community call to confirm your experience that indeed these rich disciplines are disappearing. If so, why? Is this a problem? I believe it is a problem if my recent observations are correct.

It is possible that a new focus on agile management might subsume process disciplines. I have to be honest in that while I know intellectually about agile, I have never actually practiced in this area. So in this short article, I want to briefly review the power of viewing a firm as a suite of executive, operating and support processes, demonstrate how powerful the role of time and speed can be for firms and conclude with some observations on the apparent disappearing of process disciplines.

My fascination with the process revolution happened in the 1995 to 1998 time frame during my time with Thomas Group, then one of the two top operations excellence-consulting firms in the world. I was hired in to be part of a small team that would co-develop a strategy practice that would bolt on to the firm’s powerful intellectual property and tools of operations excellence. Indeed, it took a solid twenty working days from 8:00 am to 6:00 pm to learn just the basics of process innovation and management in the Thomas Group style. This training and then my work there totally changed my views of organizational performance to this day.

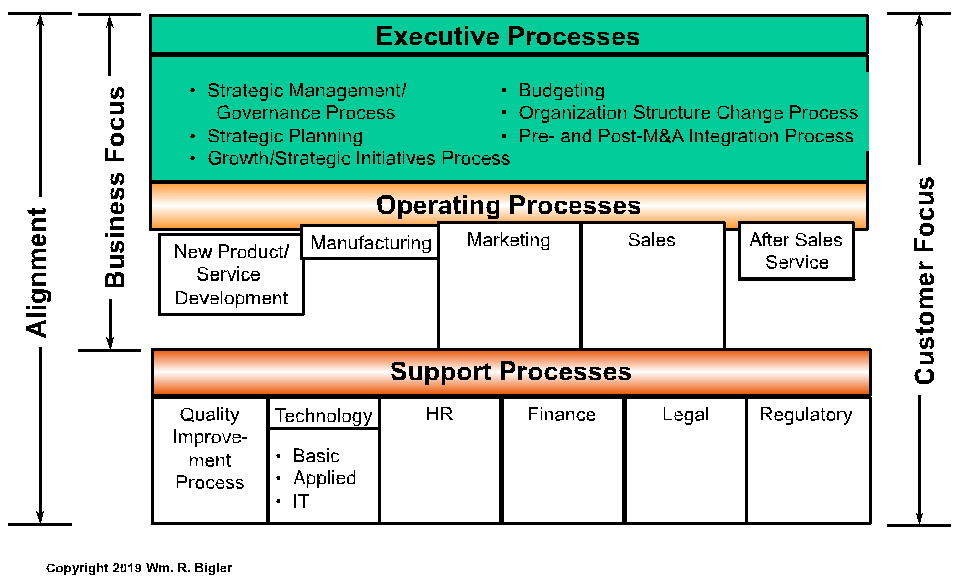

For example, we did some research about the role of time and speed in the management of their strategic initiatives in one of the leading lighting manufacturing firms who was an operations excellence client. We found it took a whopping seven years for it to complete a typical lighting strategic initiative! Management did not believe this until we demonstrated the reality by benchmarking against General Electric, Philips and two very agile smaller lighting manufacturing firms. We found the best-in-class lighting strategic initiative cycle time was fourteen months. This firm needed to take seventy months (that is 70) or 5.8 years out of its total strategic initiative cycle time to be competitive! How would it do this? Figure 1 depicts some high-level executive, operating and support processes.

Figure 1: Example Executive, Operating, and Support Processes

The usual approach then was to map the process in question. In this example, it was the Growth/Strategic Initiatives Management Process. We used old-fashioned butcher-block paper taped to a wall. Their overall process had so many steps in it that the paper was fifteen yards or forty-five feet long and three yards high. The process was mapped using usual process symbols but also with common sense notation added. Then both external and internal customers were invited in to serve as a “fishbowl” and they were armed with ten inch tall Red Flags with stickies on the backs of them representing barriers. They loved walking up and slapping a red flag somewhere on the process map where they felt a barrier existed. A “town hall” ensued to confirm the suggested barriers and how they could be removed.

The culture around process innovation and management at that time was very much like that of the quality movement from the 1960s and 1970s when particular people were not to blame for slow cycle times. The fault lay in not knowing the many counterintuitive aspects of time and speed, not using true process disciplines and faulty process design. Thus, the open discussion of barriers and their removal could happen without pointing fingers at individuals. These were always very rich and powerful discussions.

Let me give one example of the counterintuitive nature of time and speed. If a process is at capacity, adding one more piece of work to it will slow down not only that process but all processes that touch it that are also at capacity. Let me give a quick example of this. Let’s say the sales process of a firm has five salespeople working in it and they work nine hours a day. This is 225 hours of capacity in the sales process per week (5 people X 9 hours per day X five days per week). If we assess from their time and expense sheets that collectively they are working 225 hours per week, a request to do more work in that typical week will only slow everyone down. And let’s say the sales process touches the new product development process and also the after-sales-service process. These processes will slow down as well by simply adding that one piece of work to the at-capacity sales process. Achievement oriented people, not understanding these process realities, just took on extra work. They gladly would give “one for the Gipper” by trying to be seen as team players furthering their own careers by working extra hours. They did not know that what seemed like a good thing to do was actually destroying organizational performance.

Process knowledge and disciplines started around 1993 with the publication of Michael Hammer’s book The Re-engineering of the Corporation. From this high-level book, more detailed views of process management ensued.

Process knowledge and disciplines started around 1993 with the publication of Michael Hammer’s book The Re-engineering of the Corporation. From this high-level book, more detailed views of process management ensued.

Have you noticed that very few firms are engaging in this type of work anymore? I ask new clients who their “process champions” are and they look at me dumbfounded. ERP systems (think SAP and others) have their version of process work, but it is not the same as an in the trenches operations view of the most critical four or five processes in a firm at any given time point.

Where have process disciplines gone? Subsumed under agile management or ERP systems? Gone forever as a “been there and done that” kind of stance? I think if true process disciplines have left us this is a management travesty. What do you think?

This article is part of a series on what causes a firm’s value to increase.

Dr. William Bigler is the founder and CEO of Bill Bigler Associates. He is a former Associate Professor of Strategy and the former MBA Program Director at Louisiana State University at Shreveport. He was the President of the Board of the Association for Strategic Planning in 2012 and served on the Board of Advisors for Nitro Security Inc. from 2003-2005. He is the author of the 2004 book “The New Science of Strategy Execution: How Established Firms Become Fast, Sleek Wealth Creators”. He has worked in the strategy departments of PricewaterhouseCoopers, the Hay Group, Ernst & Young and the Thomas Group. He can be reached at bill@billbigler.com or www.billbigler.com.