Corporate culture is back in the news. This article outlines my approach to aligning strategy, culture and performance, which should be of interest to executives and managers of firms as well as their board of directors. This approach has been honed over thirty-five years in the field, aided by some academic research done by others and me.

Most of us have heard the phrase “culture eats strategy for lunch.” While trite, there is truth to this phrase. The phrase suggests that culture is a beast, here to stay and difficult to change for the better. This article is for those firms who find they need to change a culture either because it has become toxic or it no longer supports and aligns with the competitive strategy and has become a barrier to performance as measured by increases in the firm’s valuation or its market value.

One of the most brilliant and successful CEOs for which I was honored to work as an outside resource was Mike Waterman. Mike was a serial entrepreneur who founded, launched and grew several very successful businesses. His quote about culture from around 1991 has stuck with me ever since. “You get the culture you get or you get the one you design. And the culture you get you probably will not like.” Mike’s simple description of the culture of Simufllite, one of his very successful companies was: “We are a team of people who say what we mean, mean what we say and deliver what we promise.” There is a lot packed into these two simple quotes.

Is culture such a beast that it tends over time to the toxic? Is culture so fickle that previously “good” cultures can morph into toxic and “bad” cultures? Can cultures become to be out of alignment with strategy and a barrier to performance? My experience says yes culture can be fickle. So should we think of corporate culture as something that is set forever in a firm or one that can change? Culture at the nation, state or country level stays fixed for many generations. My view is corporate culture should change when it needs to do so.

This article takes a different view that culture is difficult to change. It can be very straightforward. In my experience, culture change is difficult because the executives and board of directors members trying to affect the change want it to happen too quickly. In my experience, culture change takes at least seven to ten years for the average mid-sized to larger firm. The average tenure of CEOs in 2020, and by ripple effects to some of the executives in their top management teams who transition out, is around five years. It is clear that any “current culture’ will outlast them. With the current call for many boards of directors to up their game, the same applies to them. Activist investors can oust them before they can contribute to effective culture change.

The reader will see that this article is cast at a level of thinking that is not in the weeds. But hopefully, it is cast at a level of abstraction that allows grasping the whole while providing keen and indispensable insights for the firm.

An Approach to Align Competitive Strategy, Culture and Firm Valuation

The outline of this article is as follows:

- Define a competitive strategy succinctly.

- Define corporate culture succinctly.

- Choose a framework that parsimoniously describes the competitive strategy so that it can be aligned with culture and performance.

- Choose an appropriate and compatible way to view increasing the value of the firm so as to link and align with the strategy and culture.

- Devise a method of Linking Competitive Strategy, Culture and Firm Valuation.

A key decision this article foists onto firms is how “surgical” one should view competitive strategy and culture change with its expected impacts on performance. Strategists for the most part do not mind such “surgicality”. Others might find it offensive. But remember, “you get the culture you get, or you get the one you design.” I have preferred to take the design route in my work with clients to the years.

1.Define A Competitive Strategy Succinctly

There are hundreds of definitions of a competitive strategy. I gave up a long time ago seeking one universally agreed to definition. So I pick and choose a definition that is fit for the purpose at hand. Thus for this article here is my definition:

A competitive strategy is a process, either explicit or informal, to seek some sort of advantage over rivals, for as long as is possible. The deliverable from this process at the end of each cycle is the firm’s strategic plan, in whatever format works for the firm. In turn, this advantage must allow the firm to earn an “economic profit”, if only for some time. An economic profit is existent if a firm earns more in free cash flow return on investment than its weighted average cost of capital. Firms with no explicit or informal strategy process, no strategic plan, no advantage and no economic profit, if only for brief periods, do not have a competitive strategy according to this definition. They have a business with an operations plan or operations approach but do not have a competitive strategy. Note these kinds of businesses can be profitable in an accounting sense. But they may not, and usually are not, profitable in an economic profit sense.

2. Define Corporate Culture Succinctly

As I have written here before, culture can be described as three interrelated components:

- a) Daily Culture – the norms of dress, norms of protocols at meetings (are people polite and eschew conflict or are they direct and combative, etc.), the norms around a conflict in general, norms of perquisites (executive parking spaces, corner offices, etc.) and the like.

- b) Climate – the degree of satisfaction among the firm’s people. Like the outside climate, is the firm’s climate hot (high levels of dissatisfaction), lukewarm, or just right where adequate levels of satisfaction exist?

- c) Deep Culture – what most people refer to as culture. These are the Deep Values that underpin Daily Culture and Climate and observed behavior by the people in the firm. One needs to be careful about Values Statements that are published on cards versus the real values that underpin observed behavior by the people in firms. They can be the same but many times they are vastly different. And this difference can cause widespread cynicism among the firm’s people.

3. Choose a Framework to Succinctly Describe the Firm’s Competitive Strategy

This step is crucial for this article. A competitive strategy (hereafter just strategy) is usually quite complex. Pundits have said for years that the people of the firm need to be able to describe the strategy clearly and easily. For this article, the strategy must be able to be described at a level where the culture can be assessed as being compatible with it or not. Remember culture can eat strategy for lunch and you get the one you get or you get the one you design.

Several candidates from my experience emerge:

- What is the “Shape of the Strategy”?

- Critical Success Factors (CSFs)

- Organizational Capabilities

- The Firm’s “Full Potential”

a) What Is the Shape of the Strategy

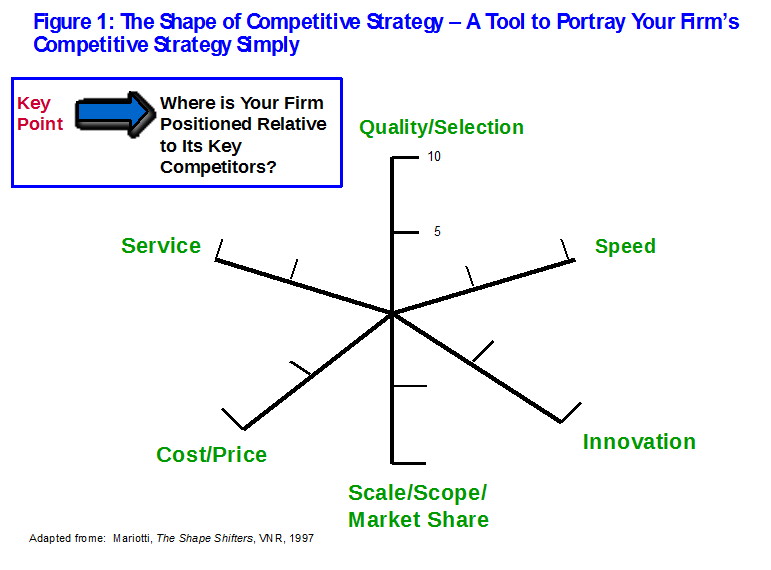

Figure 1 is from an article I have published here previously (link here):

In work with clients, I usually include more factors than this exhibit shows. But it is illustrative. One can compare the current shape of a firm’s strategy with a desired one and/or compared to rivals. It is a powerful lens on the competitive strategy. But the factors or certainly the weights of importance among them change more frequently than culture can change. Thus there is an inherent disconnect between the duration of strategy and culture.

Conclusion: The Shape of the Strategy is useful but not sufficient for assessing the alignment with the current culture or a future culture.

b) Critical Success Factors (CSFs)

There are different definitions for CSFs among different writers and even strategy academics. My definition is these are the things that adhere to industry but for which firms devise their own unique solutions. Critical Success Factors thus are the convergence of three things: 1. What do our customers want and need? 2. How do we survive the competition? 3. New, emerging industry topics that need an immediate solution. Note CSFs are related to Organizational Capabilities (discussed below). For instance, in some industries, having a Brand is a CSF. But how firms go about creating and using a brand can be unique to each firm. So are things like extreme Customer Service before and after the sale (in commodity and heavy manufacturing industries), Retention of Key or Good People (in retail), etc. But CSFs or certainly the weights of importance among them change more frequently than culture changes. Thus there is an inherent disconnect between ‘duration of strategy’ and culture.

Conclusion: CSFs are useful but not sufficient for assessing the alignment with the current culture or a future culture.

c) Organizational Capabilities

Organizational Capabilities are the mix of processes and routines that critically contribute to a firm’s competitive advantage and that advantage’s staying power (called Competitive Advantage Period in Step 4 below). Organizational Capabilities are highly complex and cross-functional combinations of processes, tools, knowledge, skills and organization. These are all put into place to deliver on the Value to Customers you seek to provide and to make your Competitive Strategy actionable. Its advantages lend staying power. Organizational Capabilities are difficult for competitors to copy in the short to mid-term.

Examples are*:

- Haier (Consumer responsive innovation, Operational excellence, Local distribution networks, On-demand production and delivery).

- Lego (Design of compelling blocks and sets for people of all ages, Operations oriented toward complexity at a reasonable cost, Management of a consumer-oriented platform, Learning-oriented brand development).

- Frito-Lay (Rapid, highly successful flavor innovation, Development of local customer and retail marketing campaigns, Direct store delivery, Consistent manufacturing and continuous improvement).

- From Strategy That Works: How Winning Companies Close the Strategy-To-Execution Gap, Paul Leinward, Casare Mainardi with Art Kleiner, HBR Press, 2016.

While Organizational Capabilities are difficult for a competitor to copy in the short to mid-term, they too can change before a culture can change.

Conclusion: Organizational Capabilities are very useful but ultimately deficient in assessing alongside the current culture or a future culture.

3.The Firm’s Full Potential

This concept is borrowed from Private Equity (link here). Full Potential describes today what can be added to the firm’s current base business over the next three to seven years. The examples below are from our comprehensive audit of new things that can be added to a firm’s base business. (Note space precludes a discussion of our approach to define a firm’s base business):

- New Versions/Upgrades of Current Products and Services to Current Customers

- New Customer Groups

- New Industries Served

- New Geographies

- New Materials Used as Inputs to Lower Costs

- New Technologies Used

- Whole New Businesses

- Re-purposing Assets

- Using More of An Asset That Sits Idle

- Etc.

The concept and reality of a firm’s Full Potential is a powerful lens for strategy and increases in the firm’s market value. However, again the changes that can happen along a firm’s journey to its Full Potential mean that a current culture will outlast those changes.

Conclusion: The Firm’s Full Potential is very useful but not sufficient for assessing the alignment with the current culture or a future culture.

As one can guess, each of the above methods to describe a current competitive strategy is necessary but not sufficient to aligning a current or future strategy to culture and ongoing performance. Step 5 will portray a method to extract the most important factors from each for a robust way to link strategy, culture and performance.

4. Choose An Appropriate and Compatible View of Increasing the Value of the Firm

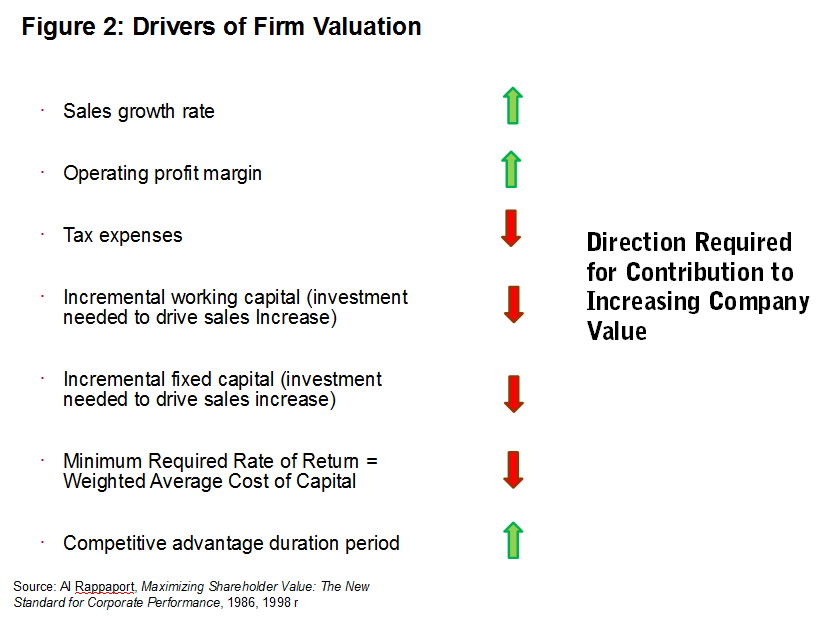

Here we can use the Drivers of Financial Value first published by Al Rappaport in 1986 (rev. 1998). Figure 2 depicts those Drivers:

I will hold off a discussion of these Drivers until Step 5, discussed next.

5. Devise A Method of Linking Competitive Strategy, Culture and Firm Valuation

If one assesses the time frames in the above analysis, one can see culture will outlast any of the time periods imbedded in the four methods to more simply describe a firm’s strategy. And culture will outlast any current performance over a reasonable time frame as well as for the nature of the business world today. The time frames from my experience are thus:

- The Shape of the Strategy – three to five years

- Critical Success Factors – three to six years

- Organizational Capabilities – four to eight years

- The Firm’s Full Potential – four to eight years

- Performance Cycle – any rolling three years

- Culture – seven to ten years

The keys to link strategy, culture and performance from my experience are:

- The depiction of the culture should be at the Deep Values level, not the Daily Culture and Climate levels. Changes in the Daily Culture that are compatible with the Deep Values can follow fairly easily. While Climate change can be difficult, programs to improve it naturally follow a set of Deep Values that ring true for the firm’s people.

- The depiction of the competitive strategy must allow some permanence but also some flexibility to change as circumstances warrant.

- The depiction of performance must also allow permanence so as to compare apples to apples.

Let’s discuss the notion of Deep Values. As I discussed at the beginning of this article, they are the real values that underpin observed behavior in a firm. Examples follow (with some references to firms who are widely known and known for that Value). Note these are not exhaustive:

- Fundamental respect for the sanctity of the individual

- People as appreciating assets and not mere expenses

- Integrity

- Truth

- Trust

- Accountability

- Insatiable curiosity

- Honesty

- Keeping promises no matter the cost or effort

- Diversity

- Teamwork

- Simplicity (i.e. no bureaucracy)

- Speed (Amazon)

- Frugality (Wal-Mart, IKEA)

- Creativity and innovation

- Fun (Southwest Airlines)

- Quality

- Future orientation

- Risk reduction or the opposite risk assimilation

- Results over effort (Danaher)

We could certainly add to this list. The key is to emphasize the five to seven deep values that are truly important for each firm (“have to haves”) and eschew those that are “nice to haves”. Another key is that the values will remain vitally important for seven to ten years. Remember Mike Waterman’s statement: “We are a team of people who say what we mean, mean what we say and deliver what we promise.” The values implied by this statement certainly underpinned observed behavior at Simuflite for at least seven to ten years. Strategy and performance changed over any ten-year period, but the culture as moored and guided by the Deep Values was enduring.

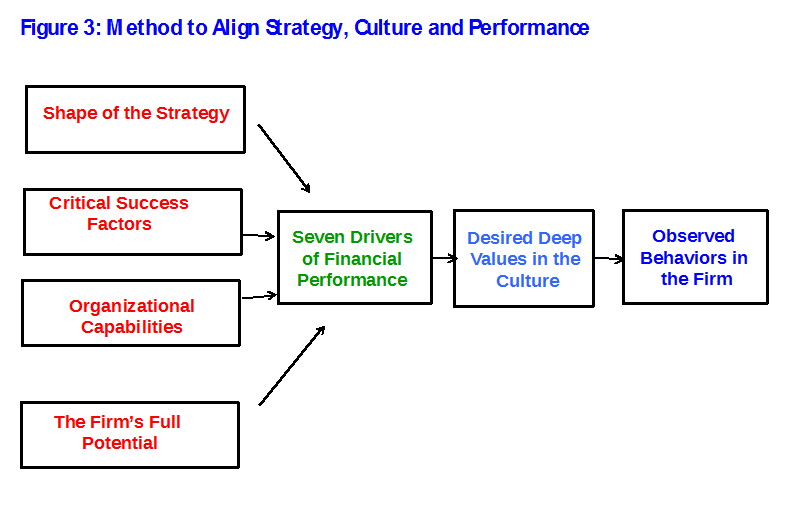

Figure 3 depicts the approach that I use to link strategy, performance and culture:

Notice the order of the flow in Figure 3. Performance as measured by the Seven Drivers of Financial Performance follows the four depictions of the Strategy, which all precede Deep Values and then the Observed Behaviors in a firm. The reason for this unconventional ordering (Financial Performance before Deep Values and Observed Behaviors) is that the values in and around Performance are just as important for establishing desired new Deep Values or confirm current Deep Values as are the four aspects of Strategy. A few examples from Figure 2 highlight this distinction:

- Sales Growth Rate – sales are Price times Quantity Sold. What are the Values that will hold firm a strategy that seeks premium prices? We know that unmoored by Deep Values that reinforce differentiation and premium prices the sales force will typically lower prices to make a sale. We can make policies that prevent unwanted price reduction. But processes plus a supporting culture are much more powerful.

- Operating Profit Margin – a Value of Frugality will seek to keep expenses as low as possible. Think of Wal-Mart here. Values around Creativity and Innovation will drive prudent decreases in expenses. Values around People As Appreciating Assets and Not Mere Expenses shine a light on the streamlined expenses that add value for the firm’s people.

- Incremental Working Capital and Fixed Capital Investment – Values of Frugality and Risk Reduction or the opposite Risk Assimilation will guide appropriate resource investment and commitment.

- Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) – Values around Risk, Frugality, Creativity and Innovation, Simplicity (i.e. no bureaucracy) will affect the WACC.

- Competitive Advantage Period (CAP) – Values around Creativity and Innovation, Teamwork, and Future Orientation will impact CAP.

Culture audits I have done over the years highlight some huge disconnects among the true Deep Values extant in firms and their impacts on desired financial performance.

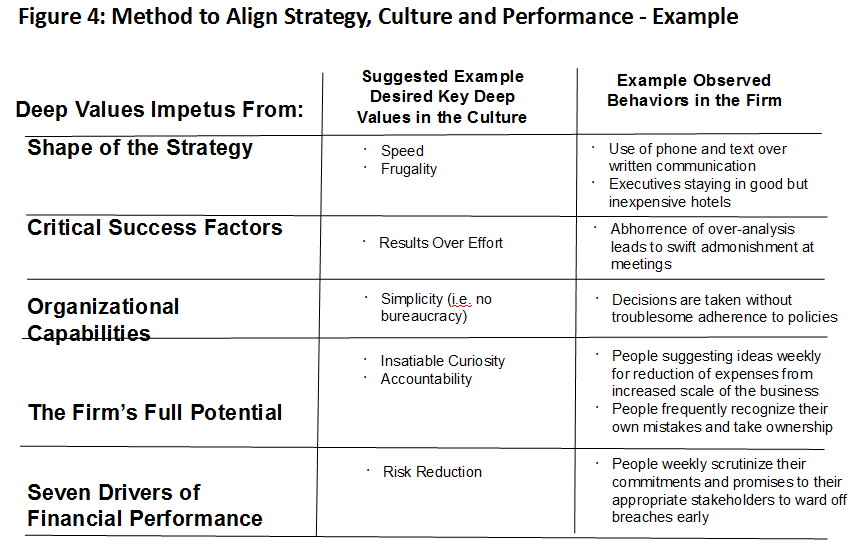

Figure 4 completes our analyses:

This part of the work is more art than science and is the “design” part of aligning strategy, performance and culture. The examples here are excerpts from a prior client. The firm’s method of competition in its competitive strategy was one of the Low-Cost Provider (LCP) (like Wal-Mart). One hopefully will see that the chosen Deep Values are consistent with the LCP method of competition and support it. The reader will hopefully see how mutually reinforcing each of the Deep Values is. The culture that derives from this example might seem “lean and keen, “no-frills” and frankly not a lot of fun. But think of Wal-Mart as the classic LCP. These Deep Values and Observed Behaviors, among many others not shown in our example, are found everywhere at Wal-Mart. The solution for a creative differentiator like BMW or Rolex, among many other differentiators, would look completely different.

The team in your firm tasked with architecting the alignment of strategy, performance and culture should go through a series of meetings to choose one or two key Deep Values from each of the five rows that will underpin the new culture. Alternatively, the Deep Values can derive from just say two of the rows depending on each firm. The insights about each Deep Value should be recorded and shared widely with the people of the firm to gain their input. After an agreement has been reached, short crisp statements describing each value or ‘groups of like values’ should be made (note example statements are not shown here). Finally, as a start, just two or three Key Behaviors for each of the chosen Deep Values should be described as examples of what the firm should expect to experience daily that demonstrates the culture to everyone in the firm and to all stakeholders who interact with the firm. Over time as your people begin to inculcate the Deep Values of the culture, the list of the Desired Behaviors can, and always does in my experience, grow.

Conclusion:

“You get the culture you get or you get the one you design. And the one you get you probably will not like.” The decision is up to the leaders in your firm. Do you want and need to become more “surgical” in the alignment of strategy, performance and culture and their ongoing management? Or will you allow culture to develop itself? The decision is indeed yours.

This article is part of a series on what causes a firm’s value to increase.

Dr. William Bigler is the founder and CEO of Bill Bigler Associates. He is a former Associate Professor of Strategy and the former MBA Program Director at Louisiana State University at Shreveport. He was the President of the Board of the Association for Strategic Planning in 2012 and served on the Board of Advisors for Nitro Security Inc. from 2003-2005. He is the author of the 2004 book “The New Science of Strategy Execution: How Established Firms Become Fast, Sleek Wealth Creators”. He has worked in the strategy departments of PricewaterhouseCoopers, the Hay Group, Ernst & Young and the Thomas Group among several others. He can be reached at bill@billbigler.com or www.billbigler.com.